Ronald J.MacDonald - First Canadian Winner of the Boston Marathon

Through some misfortune when his father died in 1888, Ronald MacDonald ultimately found his running fortune. He was 14 at the time. A couple of years later, as there were few opportunities for employment in Antigonish, Nova Scotia, his family moved to New England to live with his mother’s relative. The MacDonald family joined many other Nova Scotians to seek a better life in the United States. Moreover, Boston in those days was booming and Ronald MacDonald was able to find a job as a linesman for the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company. Later, he would work in the family lunch store.

MacDonald was fortunate to land in Cambridgeport, a suburb of Boston, since it had a great athletic club, the Cambridgeport Gymnasium Association (CGA). In 1895, MacDonald joined his brother Alexander in the club. The club was not as big as the venerable Boston Athletic Association (BAA), but it still had a strong roster of athletes. The CGA was close to Boston and Harvard which had great tracks. Moreover, in those days, Boston dominated the track and field world so the CGA had great competition to test their athletes.

When MacDonald joined the CGA, he was destined to be a distance runner. Under CGA coaching, he won his first race in July 1896, a 1-mile handicap race in Newton, Massachusetts. In his early days of training and racing, he met another Canadian, Dick Grant who was a star track athlete at Harvard. They would develop a friendship that would help define MacDonald as an accomplished runner. They both trained together and would often race each other at different distances.

In December 1897, the friends both ran the BAA cross-country amateur 4.75-mile race. Grant won in 25:58 followed by MacDonald in 27:54. MacDonald followed this strong performance by winning the 1897 7-Mile US Cross-country championships. His dedicated training led him to his first world record when in March 1898, he raced an 11-mile cross-country race. He followed that with a win at the BAA 10-mile cross-country race.

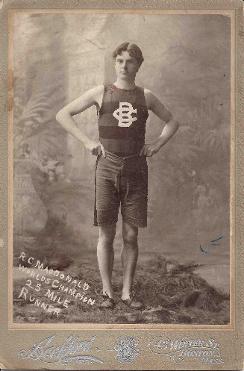

All this racing and winning positioned him well when he stepped on the starting line in Ashland, MA for the 2nd Boston Marathon on April 17, 1898. He was joined by 24 other runners, including his friend Dick Grant. MacDonald’s 5’6” 142 pounds frame was dressed in a white shirt and black trunks. The emblem of the Cambridgeport Boat Club could be seen on his shirt. He wore cycling shoes, which was quite common in those days. MacDonald had never run a marathon before then, which most likely explains his slower early pace that left him far behind the leaders. At the 15-mile of the 25-mile race, he was more than 2 miles behind the eight leaders. Soon after, he launched his attack.

With a couple of miles from the finish line, the then leader, Hamilton Gray from New York, turned around to see the curly light hair of MacDonald approaching. When MacDonald caught Gray with a little over a mile left, the two runners battled it out. Slowly, the Canadian put some distance on his rival and by the time he reached the BAA club house where the finish line was, he had gained three minutes on Gray and broken the Boston Marathon course record by 13 minutes finishing the 25 miles in 2:42:00, all without taking water. Spectators at the finish line celebrated his victory by raising him above their shoulders.

After his tremendous success in Boston, MacDonald continued training and enrolled at Boston College where they had great training facilities. He also had some bitter disappointments over the next few years. For the 1900 Olympic Games in Paris, MacDonald represented Canada, but joined the American team in their travels across the sea by ship as Canada did not send a team. MacDonald was one of eight runners in the marathon. Although he finished last, his true placing is still contested as the French, being proud of having the games in their country, apparently offered rides to the French runners who ended up top three.

Having skipped two years of the Boston Marathon, MacDonald returned to Boston in April 1901 to be amongst the 38 starters. MacDonald was confident of his abilities, having predicted since seeing Jack Caffery from Canada win the previous year, that he could break the course record set in 1900. He had not trained for the marathon the previous year, but he was ready now. The betting odds, however, were on Caffery.

In those early days of the marathon, each runner had to pass a medical exam before the race, which was not an issue for MacDonald. As the first cameras to have Boston pictures flashed, the runners waited in Ashland. After the gun went off, the first downhill mile was run in 4:40. MacDonald ran with Caffery and another Canadian, William Davis, a Mohawk. By the half-way point at Wellesley, the order had changed and Fred Hughson, another Canadian who had finished third the previous year, was leading the race. Caffery took the charge and passed Hughson. When hearing that Caffery was leading, MacDonald rallied and also passed Hughson. Soon after, MacDonald took a sponge from a spectator. This would prove to be his undoing. MacDonald started getting cramps and had to start walking. His situation got so bad that he had to retire from the race. His attending physician who followed him along the course examined the sponge at MacDonald’s home; it was apparently laced with chloroform.

MacDonald returned to Boston in 1902 to redeem himself. He was at the starting line on a sunny day, brimming with confidence that he would win again. Others were of a different opinion. One of them was Sammy Mellor from Yonkers who was trying to improve on his third-place finish from the previous year. However, MacDonald had beaten Mellor by 10 seconds the previous year at the Thanksgiving 19-Miler Hamilton Around-The-Bay race. Jack Caffery, now a two-time winner (1900 and 1901) was also planning on winning, but unfortunately for him, he retired at the starting line, leaving the race open between MacDonald and Mellor.

The two runners ran together for the first twelve miles, each testing the mettle of the other with surges. At the half-way mark, MacDonald slowed and indicated to his supporter that his stomach was causing difficulties. He then began to walk. When he got caught by John Lorden, the Irish Champion and a Cambridgeport colleague who would win the Boston Marathon in 1903, he started running with his confident stride. By the 17th mile, unfortunately, MacDonald was broken by Lorden and retired from the race. MacDonald would not return to run the Boston Marathon, although he was a handler for another runner in 1905.

MacDonald’s lack of further success in Boston was counter-balanced by some awesome performances over the next few years. He returned to Nova Scotia in 1901 when he enrolled at St. Francis Xavier University. During the next couple of years, he broke the Canadian record in the 3-Mile and 5-Mile. In an indoor race, he set a world record for the mile, although this was never ratified. In 1903, MacDonald beat Larry Brignolia, the 1899 Boston Marathon winner, in a 5-mile race. Over the course of his running career, MacDonald would win over 130 running prizes.

Not only was MacDonald a great runner, but he was also heavily involved in the sports organization. In 1902, he organized the first indoor sports meet in Eastern Canada. He even participated in the 3-mile race at that meet, defeating John Lorden. His time of 15:38 was a new Canadian Indoor record. He also wrote a book, How to Train and Win a Marathon Race. He won his last marathon in 1909 in St. John’s Newfoundland when he beat Lorden on an indoor track in a time of 3:07:50 for the 25-mile distance.

As he was producing impressive performances, he studied medicine at the university in Antigonish, followed by a degree from Tufts University in Medford outside of Boston, and some time at Harvard. His first medical practice was in Newfoundland where he spent 30 years, married, and fathered five children. He would then move back to Antigonish, Nova Scotia, to finish his medical practice and retire. His final years were not as healthy as his younger days as he suffered from diabetes; he died in 1942.

In recognition of his tremendous accomplishment in running and making Nova Scotians proud, Ronald MacDonald was inducted in the Nova Scotia Sports Hall of Fame in 1979.

Bibliography

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ronald_MacDonald_(athlete)

http://archive.boston.com/zope_homepage/sports/marathon_archive/history/1901_globe.htm

https://nsshf.com/inductee/rj-macdonald/

https://lifeasahuman.com/2012/health-fitness/running/doc-jocks-dr-ronald-j-macdonald/

https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/shr/38/2/article-p148.xml

Photo

Evan Nappen - Beckford Photo 1898

Alexis "Le Trotteur" Lapointe (1860-1924)

Before the creation of the Boston Marathon, before Pierre de Coubertin decided to re-create the Olympics with its marathon event, before any running legends could be created in North America, Canada already had its running legend. Throughout his lifetime, he would be known by a few nicknames, from “Nigaud” (idiot), to “Cheval du Nord” (Northern Horse), “Surcheval” (sur-horse), “the flying horse of the Saguenay”, but the nickname that stuck to him was “Le Trotteur” (The Trotter).

Le Trotteur was born as Alexis Lapointe in 1860 in Saint-Étienne-de-la-Malbaie, Québec. His mother, Delphine, delivered him five months premature which surprised the faculty of medicine of Laval University in Quebec. His childhood was spent on a farm with his 13 brothers and sisters. With such a large family, a small boy such as Alexis would need to come up with something to attract attention. He was a rambunctious child with loads of energy. Working on a farm was not a task for the weak and Alexis completed various chores on the farm. This would build up his stamina that would carry him far in the future.

As with most children, Alexis loved to compete against his peers, running against anyone who would challenge him. Unlike most of us, he had the talent to win most of his races. Alexis was a great runner, but he was not necessarily a handsome man. He had this habit of distorting his face and making grimaces. It is on the farm that he developed a love for horses and a love of running. Over the years, he transformed his attitude, and his love and talent for running into fame and legend.

Unfortunately, farm work was not conducive to schoolwork, so he did not have an opportunity for a formal education. His level of education was such that he was sometimes considered a “simpleton”. His smarts however were more the street smarts of those days. He was known as a joker and loved to surprise people. He was wise enough to capitalize on his talent and build himself a reputation.

Tired of farmwork, he left the farm and amongst his many occupations, he started building bread ovens. In those days, most households had an oven for bread and Alexis would travel the countryside to build these ovens.

He could often relate more closely to horses that humans. He loved to portray himself as a horse. He acted that way by neighing. He went as far as slashing himself with twigs as jockeys would do on their horses. He used the twigs to awaken his muscles before going on his famous jaunts or races. Not only could Alexis beat his friends in running races, he raced against horses, early automobiles or even trains and boats.

One of his famous legendary stories involves a race against a boat. Not being allowed to join his father on a boat trip from Bagotville to Chicoutimi, he exclaimed to his departing father, “When you arrived in Chicoutimi, I’ll be waiting for you.” Alexis ran home, picked a few belongings, slashed his legs with twigs and off he went towards Chicoutimi. The boat left at 11 in the morning and was supposed to arrive at 11pm. Alexis would then have 12 hours to complete a distance of 146 km. When the boat arrived, to his father’s surprise, Alexis was waiting for him.

His prowess for running was partially innate, but it also incorporated a tremendous amount of training which was in the form of various cross-training activities, from dancing, to jumping to hard physical labour. He had boundless energy, dancing for hours on end. He also played the harmonica.

Another story of Le Trotteur deals with his boyhood desire to join a party. Unfortunately, the party was far away, and his older friends would not let him join them on the horse carriage as they were going to see their girlfriends. When a young man has an eye for a party, he is unstoppable, especially if you had the legs and the lungs of Alexis. He apparently told himself that with a whip, he could whip himself into a fury and run like a famous horse of the time, Poppe, the Northern Horse. He made his way across fields and covered the 43 km faster than his elders. Unfortunately, the priest who was organizing the party would not allow him to join, especially as it was too early, and no one had arrived. The priest scolded Alexis and threatened to punish him for wanting to play a trick on his elders. Alexis, afraid of getting a beating, ran back home.

Even in his older years, Alexis kept up his running and surprised many. Once he started slowing down, he gained employment as a lumberjack and a construction worker. He died on June 12, 1924; legend has it while racing a locomotive. Actually, it was an accident when he stumbled trying to get out of the way of a locomotive.

In the Saguenay, the historical society has a historical display on Alexis. A series of French comic books were created about him. A painting of him racing a horse demonstrates how his legend has jumped into modern folklore. They use his legend as learning material in some Quebec schools. Songs were even written about his exploits.

Alexis Lapointe can be considered the first pioneer in Canadian distance running. Its first ultramarathoner, its first running champion, and its first running hero and legend.

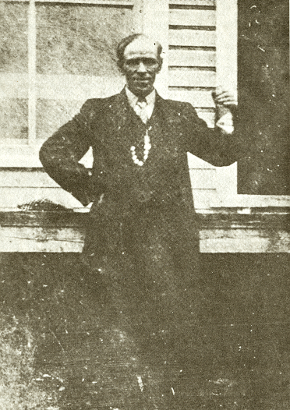

Photo from: Société d’histoire de Charlevoix

Bibliography:

- Barbeau, Marius. (1936) Kingdom of Saguenay.

- Larouche, Jean-Claude

- Barbeau, Marius. Le Saguenay légendaire, Beauchemin, Montréal, 1967

- https://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/quebec-canada/national/200911/07/01-919442-alexis-le-trotteur-remis-en-terre.php

- http://encyclobec.ca/region_projet.php?projetid=267

- http://bilan.usherbrooke.ca/bilan/pages/evenements/367.html

- https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/alexis-le-trotteur

- http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lapointe_alexis_15E.html

- http://www.ameriquefrancaise.org/en/article-412/Alexis_Lapointe,_a.k.a._Alexis_le_Trotteur_(1860-1924):_the_Man,_the_Legend.html

- Source: BARBEAU, Marius. Le Saguenay légendaire, Beauchemin, Montréal, 1967, p. 93

- https://unebellefacon.wordpress.com/2012/10/15/alexis-le-trotteur-legende/

- https://www.rds.ca/grand-club/billet/alexis-le-trotteur-des-exploits-digne-d-un-olympien-1.1242557

- https://guyboulianne.com/2020/02/01/le-legendaire-alexis-lapointe-dit-le-trotteur-cousin-germain-de-guy-boulianne/